This blog post is about the ACL 2017 paper Get To The Point: Summarization with Pointer-Generator Networks by Abigail See, Peter J Liu, and Christopher Manning. [paper] [code]

The internet age has brought unfathomably massive amounts of information to the fingertips of billions – if only we had time to read it. Though our lives have been transformed by ready access to limitless data, we also find ourselves ensnared by information overload. For this reason, automatic text summarization – the task of automatically condensing a piece of text to a shorter version – is becoming increasingly vital.

Two types of summarization

There are broadly two approaches to automatic text summarization: extractive and abstractive.

- Extractive approaches select passages from the source text, then arrange them to form a summary. You might think of these approaches as like a highlighter.

- Abstractive approaches use natural language generation techniques to write novel sentences. By the same analogy, these approaches are like a pen.

The great majority of existing approaches to automatic summarization are extractive – mostly because it is much easier to select text than it is to generate text from scratch. For example, if your extractive approach involves selecting and rearranging whole sentences from the source text, you are guaranteed to produce a summary that is grammatical, fairly readable, and related to the source text. These systems (several are available online) can be reasonably successful when applied to mid-length factual text such as news articles and technical documents.

On the other hand, the extractive approach is too restrictive to produce human-like summaries – especially of longer, more complex text. Imagine trying to write a Wikipedia-style plot synopsis of a novel – say, Great Expectations – solely by selecting and rearranging sentences from the book. This would be impossible. For one thing, Great Expectations is written in the first person whereas a synopsis should be in the third person. More importantly, condensing whole chapters of action down to a sentence like Pip visits Miss Havisham and falls in love with her adopted daughter Estella requires powerful paraphrasing that is possible only in an abstractive framework.

In short: abstractive summarization may be difficult, but it’s essential!

Enter Recurrent Neural Networks

If you’re unfamiliar with Recurrent Neural Networks or the attention mechanism, check out the excellent tutorials by WildML, Andrej Karpathy and Distill.

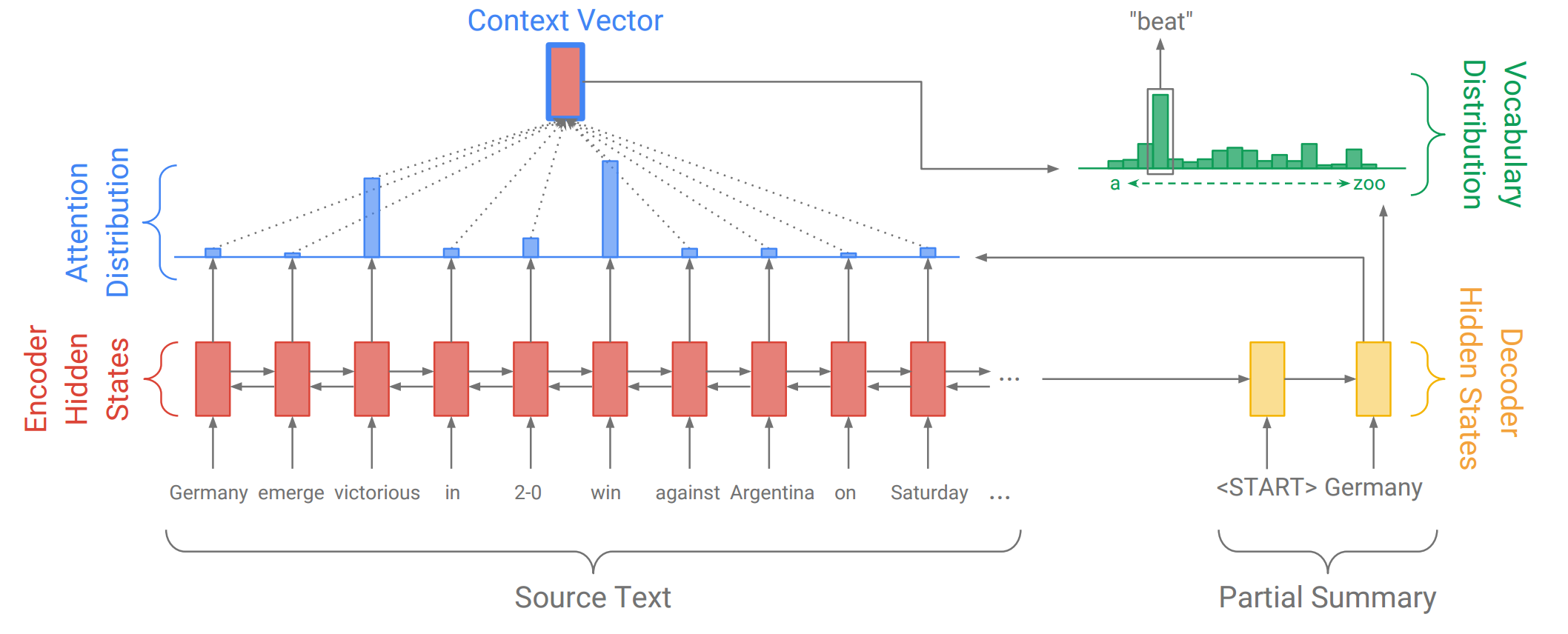

In the past few years, the Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) – a type of neural network that can perform calculations on sequential data (e.g. sequences of words) – has become the standard approach for many Natural Language Processing tasks. In particular, the sequence-to-sequence model with attention, illustrated below, has become popular for summarization. Let’s step through the diagram!

In this example, our source text is a news article that begins Germany emerge victorious in 2-0 win against Argentina on Saturday, and we’re in the process of producing the abstractive summary Germany beat Argentina 2-0. First, the encoder RNN reads in the source text word-by-word, producing a sequence of encoder hidden states. (There are arrows in both directions because our encoder is bidirectional, but that’s not important here).

Once the encoder has read the entire source text, the decoder RNN begins to output a sequence of words that should form a summary. On each step, the decoder receives as input the previous word of the summary (on the first step, this is a special <START> token which is the signal to begin writing) and uses it to update the decoder hidden state. This is used to calculate the attention distribution, which is a probability distribution over the words in the source text. Intuitively, the attention distribution tells the network where to look to help it produce the next word. In the diagram above, the decoder has so far produced the first word Germany, and is concentrating on the source words win and victorious in order to generate the next word beat.

Next, the attention distribution is used to produce a weighted sum of the encoder hidden states, known as the context vector. The context vector can be regarded as “what has been read from the source text” on this step of the decoder. Finally, the context vector and the decoder hidden state are used to calculate the vocabulary distribution, which is a probability distribution over all the words in a large fixed vocabulary (typically tens or hundreds of thousands of words). The word with the largest probability (on this step, beat) is chosen as output, and the decoder moves on to the next step.

The decoder’s ability to freely generate words in any order – including words such as beat that do not appear in the source text – makes the sequence-to-sequence model a potentially powerful solution to abstractive summarization.

Two Big Problems

Unfortunately, this approach to summarization suffers from two big problems:

Problem 1: The summaries sometimes reproduce factual details inaccurately (e.g. Germany beat Argentina 3-2). This is especially common for rare or out-of-vocabulary words such as 2-0.

Problem 2: The summaries sometimes repeat themselves (e.g. Germany beat Germany beat Germany beat…)

In fact, these problems are common for RNNs in general. As always in deep learning, it’s difficult to explain why the network exhibits any particular behavior. For those who are interested, I offer the following conjectures. If you’re not interested, skip ahead to the solutions.

Explanation for Problem 1: The sequence-to-sequence-with-attention model makes it too difficult to copy a word w from the source text. The network must somehow recover the original word after the information has passed through several layers of computation (including mapping w to its word embedding).

In particular, if w is a rare word that appeared infrequently during training and therefore has a poor word embedding (i.e. it is clustered with completely unrelated words), then w is, from the perspective of the network, indistinguishable from many other words, thus impossible to reproduce.

Even if w has a good word embedding, the network may still have difficulty reproducing the word. For example, RNN summarization systems often replace a name with another name (e.g. Anna → Emily) or a city with another city (e.g. Delhi → Mumbai). This is because the word embeddings for e.g. female names or Indian cities tend to cluster together, which may cause confusion when attempting to reconstruct the original word.

In short, this seems like an unnecessarily difficult way to perform a simple operation – copying – that is a fundamental operation in summarization.

Explanation for Problem 2: Repetition may be caused by the decoder’s over-reliance on the decoder input (i.e. previous summary word), rather than storing longer-term information in the decoder state. This can be seen by the fact that a single repeated word commonly triggers an endless repetitive cycle. For example, a single substitution error Germany beat Germany leads to the catastrophic Germany beat Germany beat Germany beat…, and not the less-wrong Germany beat Germany 2-0.

Easier Copying with Pointer-Generator Networks

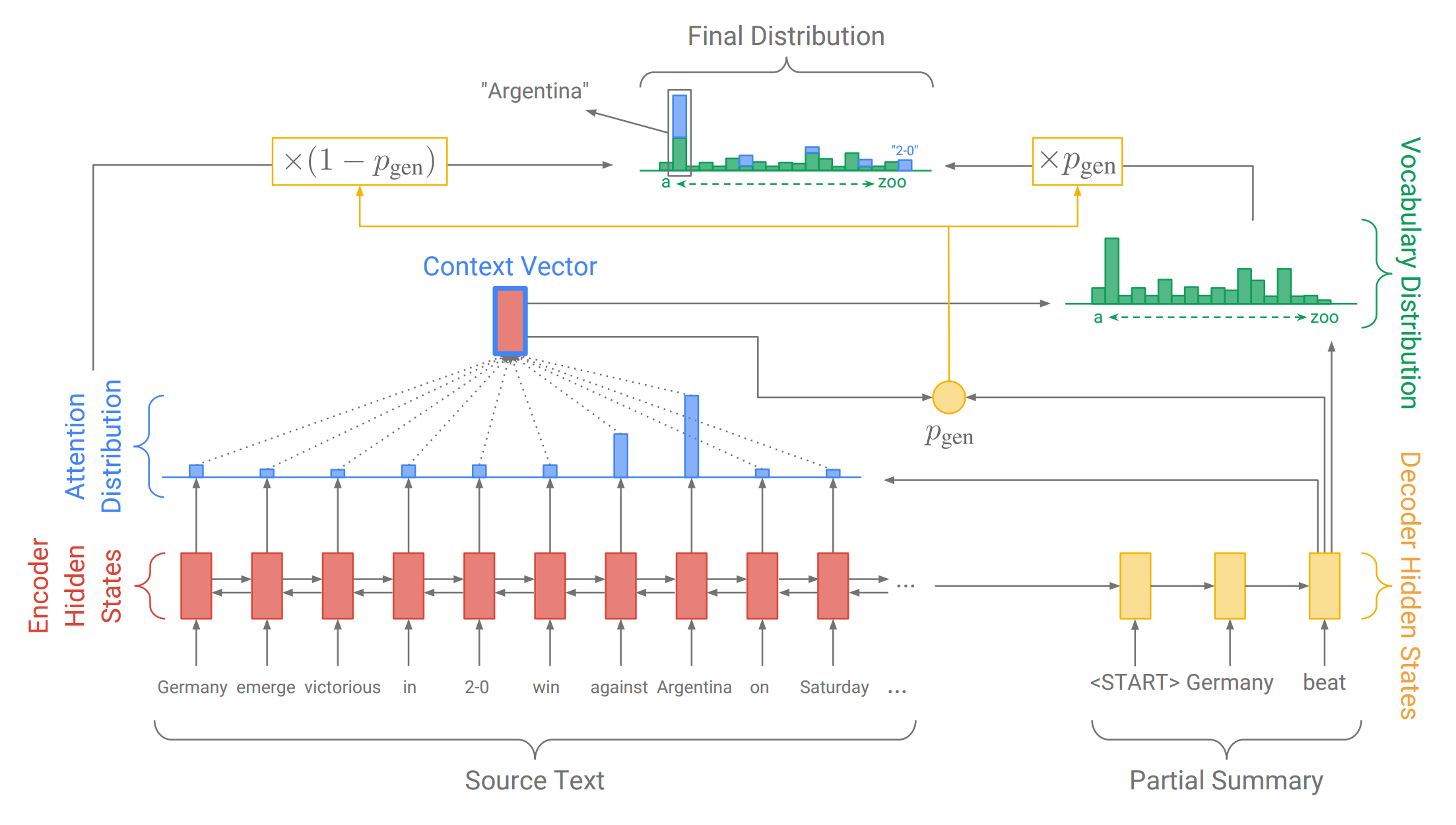

Our solution for Problem 1 (inaccurate copying) is the pointer-generator network. This is a hybrid network that can choose to copy words from the source via pointing, while retaining the ability to generate words from the fixed vocabulary. Let’s step through the diagram!

This diagram shows the third step of the decoder, when we have so far generated the partial summary Germany beat. As before, we calculate an attention distribution and a vocabulary distribution. However, we also calculate the generation probability , which is a scalar value between 0 and 1. This represents the probability of generating a word from the vocabulary, versus copying a word from the source. The generation probability is used to weight and combine the vocabulary distribution (which we use for generating) and the attention distribution (which we use for pointing to source words ) into the final distribution via the following formula:

This formula just says that the probability of producing word is equal to the probability of generating it from the vocabulary (multiplied by the generation probability) plus the probability of pointing to it anywhere it appears in the source text (multiplied by the copying probability).

Compared to the sequence-to-sequence-with-attention system, the pointer-generator network has several advantages:

- The pointer-generator network makes it easy to copy words from the source text. The network simply needs to put sufficiently large attention on the relevant word, and make sufficiently large.

- The pointer-generator model is even able to copy out-of-vocabulary words from the source text. This is a major bonus, enabling us to handle unseen words while also allowing us to use a smaller vocabulary (which requires less computation and storage space).

- The pointer-generator model is faster to train, requiring fewer training iterations to achieve the same performance as the sequence-to-sequence attention system.

In this way, the pointer-generator network is a best of both worlds, combining both extraction (pointing) and abstraction (generating).

Eliminating Repetition with Coverage

To tackle Problem 2 (repetitive summaries), we use a technique called coverage. The idea is that we use the attention distribution to keep track of what’s been covered so far, and penalize the network for attending to same parts again.

On each timestep of the decoder, the coverage vector is the sum of all the attention distributions so far:

In other words, the coverage of a particular source word is equal to the amount of attention it has received so far. In our running example, the coverage vector may build up like so (where yellow shading intensity represents coverage):

Lastly, we introduce an extra loss term to penalize any overlap between the coverage vector and the new attention distribution :

This discourages the network from attending to (thus summarizing) anything that’s already been covered.

Example Output

Let’s see a comparison of the systems on some real data! We trained and tested our networks on the CNN / Daily Mail dataset, which contains news articles paired with multi-sentence summaries.

The example below shows the source text (a news article about rugby) alongside the reference summary that originally accompanied the article, plus the three automatic summaries produced by our three systems. By hovering your cursor over a word from one of the automatic summaries, you can view the attention distribution projected in yellow on the source text. This tells you where the network was “looking” when it produced that word.

For the pointer-generator models, the value of the generation probability is also visualized in green. Hovering the cursor over a word from one of those summaries will show you the value of the generation probability for that word.

Note: you may need to zoom out using your browser window to view the demo all on one screen. Does not work for mobile.

Source Text

Reference summary

Sequence-to-sequence + attention summary

Pointer-generator summary

Pointer-generator model + coverage summary

Observations:

- The basic sequence-to-sequence system is unable to copy out-of-vocabulary words like Saili, outputting the unknown token [UNK] instead. By contrast the pointer-generator systems have no trouble copying this word.

- Though this story happens in New Zealand, the basic sequence-to-sequence system mistakenly reports that the player is Dutch and the team Irish – perhaps reflecting the European bias of the training data. When it produced these words, the network was mostly attending to the names Munster and Francis – it seems the system struggled to copy these correctly.

- For reasons unknown, the phrase a great addition to their backline is replaced with the nonsensical phrase a great addition to their respective prospects by the basic sequence-to-sequence system. Though the network was attending directly to the word backline, it was not copied correctly.

- The basic pointer-generator summary repeats itself, and we see that it’s attending to the same parts of the source text each time. By contrast the pointer-generator + coverage model contains no repetition, and we can see that though it uses the word Saili twice, the network attends to completely different occurrences of the word each time – evidence of the coverage system in action.

- The green shading shows that the generation probability tends to be high whenever the network is editing the source text. For example, is high when the network produces a period to shorten a sentence, and when jumping to another part of the text such as will move to the province… and was part of the new zealand under-20 side….

- For all three systems, the attention distribution is fairly focused: usually looking at just one or two words at a time. Errors tend to occur when the attention is more scattered, indicating that perhaps the network is unsure what to do.

- All three systems attend to Munster and Francis when producing the first word of the summary. In general, the networks tend to seek out names to begin summaries.

So, is abstractive summarization solved?

Not by a long way! Though we’ve shown that these improvements help to tame some of the wild behavior of Recurrent Neural Networks, there are still many unsolved problems:

- Though our system produces abstractive summaries, the wording is usually quite close to the original text. Higher-level abstraction – such as more powerful, compressive paraphrasing – remains unsolved.

- Sometimes the network fails to focus on the core of the source text, instead choosing to summarize a less important, secondary piece of information.

- Sometimes the network incorrectly composes fragments of the source text – for example reporting that Argentina beat Germany 2-0 when in fact the opposite was true.

- Multi-sentence summaries sometimes fail to make sense a whole, for example referring to an entity by pronoun (e.g. she) without first introducing it (e.g. German Chancellor Angela Merkel).

I believe the most important direction for future research is interpretability. The attention mechanism, by revealing what the network is “looking at”, shines some precious light into the black box of neural networks, helping us to debug problems like repetition and copying. To make further advances, we need greater insight into what RNNs are learning from text and how that knowledge is represented.

But that’s a story for another day! In the meantime, check out the paper for more details on our work.